Hosted Execution of smaller code snippets with Roslyn

Posted by Filip Ekberg on 08 Dec 2011

Lately a lot of my time has been spent on playing around with Roslyn, if you have no idea what Roslyn is I suggest that you go and >read my previous posts on it. One of the things that I challenged myself into doing was creating some soft of service that could execute a code snippet like the interactive window and give me the result back to me. First off I just want to say that I completely Love the C# Interactive Window, I've got two posts dedicated to it already!

With that said, let's step on the gas a bit, a while back there was a blog post about how to replicate the c# interactive window outside visual studio, hence creating a REPL that didn't require you to run visual studio. This is pretty awesome if you ask me. However the code that you write into the REPL is assumed to be trusted, it doesn't run in a completely different security context which makes it dangerous if you want to expose it to others.

I've been hooked on IRC for many, many years so it came quite naturally to me that I wanted to create an IRC client (bot) that I could send commands to and have the result printed back to me. For those that don't know what IRC is, it's short for "Internet Relay Chat". Basically you can join rooms and have discussions and you can have private conversations and so on. I will only focus on the Roslyn parts here.

So what I wanted to achieve was the following:

- Create an IRC robot that when spoken to, evaluates the message as C# code and prints the result

- The code needs to be run in a secure sandbox

The first one was pretty easy to solve, since I already had code for an IRC client I just needed to do the roslyn integration. The basic idea here is that you take a code snippet, you tell the roslyn script engine to compile this submission into a memory stream and then you execute that in a separate assembly.

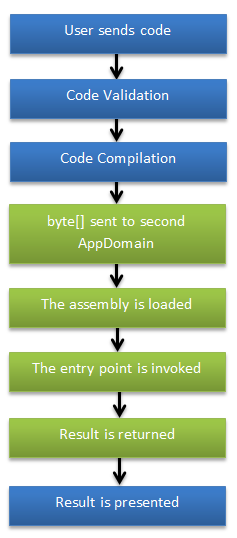

Let's take a look at a diagram of this:

All the green boxes indicate that we are in a secure sandbox and we load and run the code in a low trust AppDomain. Before we get ahead of ourselves, let's look at how I tried solving the actual code execution before trying to make it secure.

This is a pretty common work pattern, you make something work, you make it fail, you make it work again and then you make it better. Let's start look at some code!

So the first thing that we need to execute a script is the ScriptEngine and then you will need a Session to keep track on everything. This is pretty simple, let's say that we want to execute the following code:

var x = 10;

x==10

Running this in the C# Interactive Window would just print "True", let's try to get the same result here like this:

var engine = new ScriptEngine();

var session = Session.Create();

engine.Execute("var x = 10; x == 10", session)

If we print the result of this execution it will indeed say "True". Let us just step away from the keyboard and mouse for a moment, take a deep breath and just think about how amazing this is, this means that we can actually let people write scripts for our applications that! For all you gamers out there, think of LUA and how many plugins there are for world of warcraft. Anyways, back to the code execution.

The biggest problem with this is that it runs in the same assembly as we are and we don't want to load a sandbox and allow it to use roslyn directly, because roslyn itself needs full trust for the compilation. Keep in mind, we're still playing with the CTP, much can change when the final release is out there.

Now this means that we can't use Execute because we want it to be a bit more secure than this, we actually need it to run in another AppDomain. So I converted the above and used the method CompileSubmission<T> instead, this allowed me to compile the code snippet into a memory stream! With some changes of the code, I ended up with something like this:

using (var memoryStream = new MemoryStream())

{

engine.CompileSubmission<object>("var x = 10; x == 10", session).Compilation.Emit(memoryStream);

var assembly = memoryStream.ToArray();

}

To load this into a new AppDomain, you simply do myAppDomain.Load(assembly) however, we are still not quite there yet, we need to have a look at what is generated from the compilation! So instead of using a memory stream I used a file stream and saved the assembly to disk and then inspected it with Reflector 7, this is what ended up in the assembly:

using Microsoft.CSharp.RuntimeHelpers;

using Roslyn.Scripting;

using System;

public sealed class Submission#0

{

public int x;

public Submission#0(Session session, ref object submissionResult)

{

SessionHelpers.SetSubmission(session, 0, this);

this.x = 10;

submissionResult = (this.x == 10);

}

public static object <Factory>(Session session)

{

object result;

new Submission#0(session, ref result);

return result;

}

}

This all look very good, until you really think about what happens when you do Cross-AppDomain things, everything that is sent to another app domain needs to be serializable and Session is not. By this time I got some help from some never nice guys over at Microsoft which really helped me along the way.

Again, keep in mind that this is only CTP, I hope that Roslyn will contain something that will make hosted execution much easier in the future.

So this means that we can't use ScriptEngine at all, we need to take a look at something else, we actually have to do a "real" compilation using a compiler object from Compilation.Create(). This will also let us emit our output to a memory stream. However we are presented with some more problems, the code that is executed will be inside an internal class so we need to send another class that actually instantiates it and gives us the value.

Sounds confusing? It might get a bit clearer in a little bit.

The "other" class that I compile with the script is this one:

public class EntryPoint

{

public static object Result { get; set; }

public static void Main()

{

Result = Script.Eval();

}

}

The name Script is actually the name of the class that will hold our "script", you can change that name if you'd like. As you can se all we are doing here is setting our public static variable called Result to whatever Eval() will return.

This brings us to the interesting part. I had to make some compromises, instead of just being able to write "1 == 2" I now have to write "return 1 == 2;" it's not really a hassle once you get use to it. So what does Eval() look like? It's actually a method that I had to define, it will be inside the Script class and it will look like this:

var script = "public static object Eval() {" + code + "}";

As you can see I am actually concatenating some code variable into the method, which means that it will look like this with the above example:

public static object Eval()

{

return 1 == 2;

}

Which means that so far I had something like this:

public object Execute(string code)

{

const string entryPoint =

"using System.Reflection; public class EntryPoint { public static object Result {get;set;} public static void Main() { Result = Script.Eval(); } }";

var script = "public static object Eval() {" + code + "}";

}

Before I actually compile this code I want to create my sandbox, the reason for me creating the sandbox before I compile is because I want to load some assemblies into the sandbox so I can use the file locations of the assemblies when I am compiling. To create the sandbox I simple used this method:

private static AppDomain CreateSandbox()

{

var e = new Evidence();

e.AddHostEvidence(new Zone(SecurityZone.Internet));

var ps = SecurityManager.GetStandardSandbox(e);

var security = new SecurityPermission(SecurityPermissionFlag.Execution);

ps.AddPermission(security);

var setup = new AppDomainSetup { ApplicationBase = Path.GetDirectoryName(Assembly.GetExecutingAssembly().Location) };

return AppDomain.CreateDomain("Sandbox", null, setup, ps);

}

This will give us a new AppDomain that we can use that has a trust level of Internet, which will not allow for any type of I/O and many other things.

So my next step is to create the sandbox and reference System and System.Core inside it.

var sandbox = CreateSandbox();

var core = sandbox.Load("System.Core, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=b77a5c561934e089");

var system = sandbox.Load("System, Version=4.0.0.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=b77a5c561934e089");

Next up is to create the actual compilation object, this is how that works:

- Select what type of assembly it is

- Set the namespaces that you want to use

- Include all the syntax trees that you want to compile into the assembly

- Set which references to include in the compilation

The last one is why we loaded the Assemblies before hand, the references are referenced using a MetadataReference and unfortunately there is not one that successfully takes a fully qualified name (that works.). So this is a work around until that issue is fixed. So this is how it ends up:

var compilation = Compilation.Create("foo", new CompilationOptions( assemblyKind: AssemblyKind.ConsoleApplication,

usings: ReadOnlyArray<string>.CreateFrom(

new[] {

"System",

"System.IO",

"System.Net",

"System.Linq",

"System.Text",

"System.Text.RegularExpressions",

"System.Collections.Generic" })),

new[]

{

SyntaxTree.ParseCompilationUnit(entryPoint),

SyntaxTree.ParseCompilationUnit(script, options: new ParseOptions(kind: SourceCodeKind.Interactive))

},

new MetadataReference[] {

new AssemblyFileReference(typeof(object).Assembly.Location),

new AssemblyFileReference(core.Location),

new AssemblyFileReference(system.Location)

});

By now we should be ready to actually compile! This looks almost exactly like what we did before:

byte[] compiledAssembly;

using (var output = new MemoryStream())

{

var emitResult = compilation.Emit(output);

if (!emitResult.Success)

{

}

compiledAssembly = output.ToArray();

}

As you can see here, we've actually got an emit result that we can use to see if the compilation failed or not, which would be appropriate to tell the person sending code for execution. You can get the errors like this:

emitResult.Diagnostics.Select(x => x.Info.GetMessage());

Now the next step is to actually load this assembly into our sandbox, but to do that, we need to do one more thing. We need to create a class that is a MarshalByRefObject, we need this proxy in order to load the compiled assembly into the sandbox.

It simple looks like this:

public sealed class ByteCodeLoader : MarshalByRefObject

{

public ByteCodeLoader()

{

}

public object Run(byte[] compiledAssembly)

{

var assembly = Assembly.Load(compiledAssembly);

assembly.EntryPoint.Invoke(null, new object[] { });

var result = assembly.GetType("EntryPoint").GetProperty("Result").GetValue(null, null);

return result;

}

}

As you can see there is already code in the Run-method to actually get the Property-value of Result. If you remember the class EntryPoint looked, you know that we first need to create an instance of it and then get the property in order for it to actually be set. Let's keep going, we've still got a couple of more things to do before this is all set.

What we can do now is actually create an instance of the ByteCodeLoader inside the sandbox AppDomain and then call Run(), you can see this as some sort of proxy:

var loader =

(ByteCodeLoader)Activator.CreateInstance(sandbox, typeof(ByteCodeLoader).Assembly.FullName, typeof(ByteCodeLoader).FullName)

.Unwrap();

Now we are actually all set! We can run this code inside our sandbox app domain! What happens if someone would execute this code:

while(true){} return 1;

This would both compile and run fine. To avoid this, let's run the code inside a thread and abort it after a fair amount of time:

var scriptThread = new Thread(() =>

{

try

{

result = loader.Run(compiledAssembly);

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

result = ex.Message;

}

});

scriptThread.Start();

if (!scriptThread.Join(6000))

{

scriptThread.Abort();

AppDomain.Unload(sandbox);

}

After we're done, we just Unload the AppDomain and all it's referenced assemblies to free up memory.

By this time, I thought everything was running smoothly, until someone tried this:

Action f = null; f = () => { f(); f(); }; f(); return 1;

This will actually cause a StackOverflowException and in .NET 2.0 and above, you cannot recover from that. This felt of course as being back on square one, the things is that if you have a child AppDomain and it throws a StackOverflowException it will travel back to the parent and be thrown there as well. The only solution is to run this inside another process.

So I figured that the best way to do this is to run this as a Windows Service and communicate with the system over a named pipe! The best part is that the code execution can still be intact, we don't need to change that! We're going to use WCF to communicate with our named pipe and the contract will look like this:

using System.ServiceModel;

[ServiceContract(Namespace = "http://example.com/RoslynCodeExecution")]

interface ICommandService

{

[OperationContract]

string Execute(string code);

}

Pretty simple, but there's not really much more to the contract, we just want to execute code and get a result back to us. So let's have a look at the actual implementation, what we want to do here is that we want to run our code execution and get an unformatted object back then we want to return a formatted result back over the pipe, so this is how I did the implementation of the CommandServer:

[ServiceBehavior(InstanceContextMode = InstanceContextMode.Single)]

internal class CommandService : ICommandService

{

public string Execute(string code)

{

var engine = new CodeExecuter();

try

{

var unformatted = engine.Execute(code);

var formatter = new ObjectFormatter(maxLineLength: 350);

return formatter.FormatObject(unformatted);

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

}

return string.Empty;

}

}

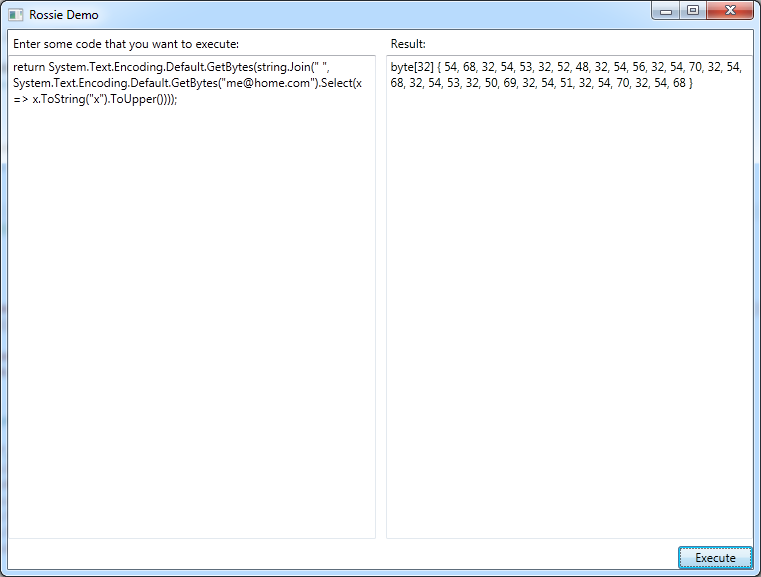

Using the object formatter means that if it returns an array of bytes, the actual string we will get back will look like this:

byte[32] { 54, 68, 32, 54, 53, 32, 52, 48, 32, 54, 56, 32, 54, 70, 32, 54, 68, 32, 54, 53, 32, 50, 69, 32, 54, 51, 32, 54, 70, 32, 54, 68 }

Now all we need to do is start the named pipe and listen to it like this:

static class CommandServer

{

private static readonly Uri ServiceUri = new Uri("net.pipe://localhost/Pipe");

private const string PipeName = "RossieEngineService";

private static readonly CommandService Service = new CommandService();

private static ServiceHost _host;

public static void Start()

{

_host = new ServiceHost(Service, ServiceUri);

_host.AddServiceEndpoint(typeof(ICommandService), new NetNamedPipeBinding(), PipeName);

_host.Open();

}

public static void Stop()

{

if ((_host == null) || (_host.State == CommunicationState.Closed)) return;

_host.Close();

_host = null;

}

}

This is just standard code to get the named pipe running and all the actual service will do now is this:

var thread = new Thread(CommandServer.Start);

thread.Start();

Play with the thought that the service is running nicely now, it might have for days and then someone decides to run code that results in a StackOverflowException, what will happen? By the looks of it, it will still not recover from it. Let's take a look at a changed diagram to figure out how to solve this, because what will happen is that the Windows Service will just be marked as Not Running

So this means that we actually don't have to change anything on either the service or the code executor! We just need to think about how we use this from the client side. The first thing we need to do is to copy ICommandService into the client project.

We will also need this in the client to be able to use the named pipe:

private static readonly Uri ServiceUri = new Uri("net.pipe://localhost/Pipe");

private const string PipeName = "RossieEngineService";

private static readonly EndpointAddress ServiceAddress = new EndpointAddress(string.Format(CultureInfo.InvariantCulture, "{0}/{1}", ServiceUri.OriginalString, PipeName));

private static ICommandService _serviceProxy;

Then we add a method that will create a new ChannelFactory<T> each time we invoke it, this way we can make sure that the channel is always open:

private static void StartCodeService()

{

var service = new ServiceController("Rossie Engine Service");

if (service.Status != ServiceControllerStatus.Running)

{

service.Start();

service.WaitForStatus(ServiceControllerStatus.Running);

}

_serviceProxy = ChannelFactory<ICommandService>.CreateChannel(new NetNamedPipeBinding(), ServiceAddress);

}

As you can see it also checks if the service is running, if it's not, we start it and wait for it to start. This will however present us with a new problem, in order to start a service the client application needs to run with administrator privileges. Now all that is left for us to do is to start the code service and execute code!

So this is the final piece of code that will look like this:

StartCodeService();

var serviceResult = _serviceProxy.Execute(code);

Where code is some variable we've filled up with code to run. I get that this has been a lot to take in, so the entire project is hosted on GitHub, it's open source, go and have fun with it!

I'll leave you with a final demo of the demo application that you can download from the github project:

I hope you found this interesting, if you have any thoughts please leave a comment below!

Filip Ekberg is a Principal Consultant at fekberg AB in the country with all the polar bears, Microsoft C# MVP, author of a self-published C# programming book, Pluralsight author and overall in love with programming.

Filip Ekberg is a Principal Consultant at fekberg AB in the country with all the polar bears, Microsoft C# MVP, author of a self-published C# programming book, Pluralsight author and overall in love with programming.