Microsoft Compiler Platform aka Roslyn

Posted by Filip Ekberg on 31 Oct 2014

A bit over a year ago I wrote and talked about Roslyn a fair bit, a lot has happened in this last year both in terms of the progression of the C# language and the compiler platform itself. Most notably is probably the decision to make the compiler platform open source which happened earlier this year. With the decision to open source the compiler platform, it meant that the community could take part of what is the next version of the languages, what the compilers looks like under the hood and most interesting of them all: the decision making behind language features and directions of the project.

I will not go into detail on the language features of C# 6.0 as there is an article published by me in the DNC Magazine on this. Instead we will take a look at how we can use what is available to us today.

Disclaimer: The APIs discussed below can, and most likely will change before the final release. You can follow the changelogs on roslyn.codeplex.com.

The idea is that we pass a chunk of code to the compiler and then we have the opportunity to analyse the semantics and the syntax that is produced by the compiler, before telling it to emit the code and make it runnable. You might be asking yourself why you would want to analyse code yourself, there may be multiple reasons for you to do so. Consider you are working on a project where you have some very specific code guidelines, in order for your team to adapt to these guidelines you may write a simply plugin using the compiler platform that analyses the code and based on passing or failing the guideline, it may fail the build for your or give you some indication that you need to change it.

The idea is that we pass a chunk of code to the compiler and then we have the opportunity to analyse the semantics and the syntax that is produced by the compiler, before telling it to emit the code and make it runnable. You might be asking yourself why you would want to analyse code yourself, there may be multiple reasons for you to do so. Consider you are working on a project where you have some very specific code guidelines, in order for your team to adapt to these guidelines you may write a simply plugin using the compiler platform that analyses the code and based on passing or failing the guideline, it may fail the build for your or give you some indication that you need to change it.

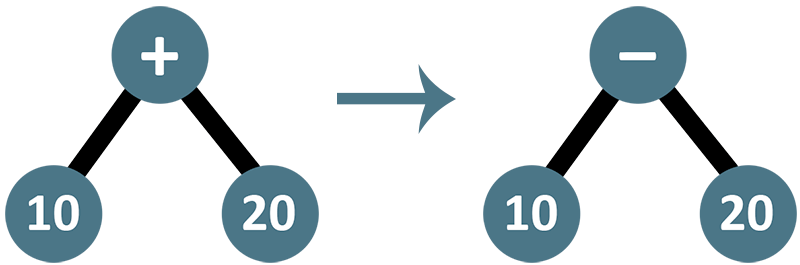

Another scenario is aspect oriented programming, you may want to analyse and when finding something particular, modifying the behaviour. I did a talk in 2013 about how to utilize this to create a fairly interesting plugin system. In this talk I used PostSharp to do the aspect oriented programming parts, but this could just as well have been done with the Microsoft Compiler Platform, Roslyn, instead. Take a look at the following image, here we have two representations as trees of an expression saying 10 + 20. The right hand tree shows how we have replaced the + with a -.

This very simply example does not rightfully show you the power of what the compiler platform allows you to do, your possibilities are somewhat endless. Consider another scenario, where you use the compiler platform to find all method calls to a certain method, you replace the method call with a custom block of code that adds some logging, the following code sample shows an example of this.

// Original method call

var result = MyMethod(10);

// Re-written method call using Roslyn

Debug.WriteLine("Calling {0} with first parameter value {1}", "MyMethod", 10);

var result = MyMethod(10);

Debug.WriteLine("Call to {0} finished", "MyMethod");

Imagine also being able to add timers in here to see how long certain calls take, of course the analysis tools in Visual Studio still enables you to do so. Sometimes though you might want to get this type of data from a production environment, then you could just have a custom compilation that would replace all these method calls to include more logging, timing and so forth.

Performing the actual replacing of nodes may not be as trivial as you expect though, it does take some understanding of the compiler platform and what the representation of code looks like from the compilers perspective. On a very abstract and basic level, the tree that represents a code block is immutable, what you do is that you tell the node that you are currently inspecting (the +) that you want to replace it with another node (the -). This will return a new tree representation that you can include in your compilation. You need to think of the replacement of nodes as replacements of a string, it will not do in-place replacing, but the structure is immutable!

There are previous articles, and also my book that covers the basic understanding and how to do the code analysis with Roslyn, there has been changes to their APIs and changes that makes it suitable to re-iterate how it works.

Compiling code with the Compiler Platform aka Roslyn

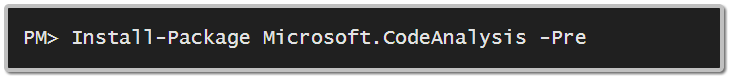

To use the new Compiler Platform we first need to install it, this is easily done using NuGet. This means that we can, in a normal console application, web application or even WPF application, just pull in the files via the NuGet package manager. It is a pre-release so do not forget to append the attribute for that, as you see in the following image, the package Microsoft.CodeAnalysis is installed via the NuGet package manager.

Installing this will bring in a couple of other packages as well:

PM> Install-Package Microsoft.CodeAnalysis -Pre

Attempting to resolve dependency 'Microsoft.CodeAnalysis.CSharp.Workspaces (≥ 0.7.4052301-beta)'.

Attempting to resolve dependency 'Microsoft.CodeAnalysis.Workspaces.Common (≥ 0.7.4052301-beta)'.

Attempting to resolve dependency 'Microsoft.CodeAnalysis.Common (≥ 0.7.4052301-beta)'.

Attempting to resolve dependency 'Microsoft.Bcl.Immutable (≥ 1.1.20-beta)'.

Attempting to resolve dependency 'Microsoft.Bcl.Metadata (≥ 1.0.11-alpha)'.

Attempting to resolve dependency 'Microsoft.CodeAnalysis.CSharp (≥ 0.7.4052301-beta)'.

Attempting to resolve dependency 'Microsoft.CodeAnalysis.VisualBasic.Workspaces (≥ 0.7.4052301-beta)'.

Attempting to resolve dependency 'Microsoft.CodeAnalysis.VisualBasic (≥ 0.7.4052301-beta)'.

This will let us do all sorts of things such as analysing, replacing and emitting code to make it runnable.

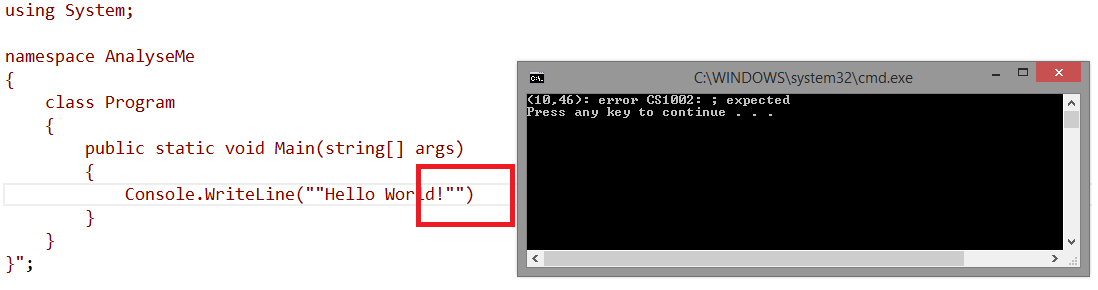

The first thing that we will add in this console application to test the power of Roslyn is the code that we want to compile. In this case I just want to add a code snippet that prints something to the console and says the standard Hello World. As seen in the following code snippet, we are simply doing this as an inline string, this could just as well have been a file on disk .

var code = @"

using System;

namespace AnalyseMe

{

class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

Console.WriteLine(""Hello World!"");

}

}

}";

The intention here is to compile the code, look for any possible errors and then execute the file on disk. We can perform the final executions by hand, but do the rest with Roslyn. We are ready to ask for a syntax tree representation of our code, as the code snippet is C# we can use the static method ParseText on the class CSharpSyntaxTree:

var tree = CSharpSyntaxTree.ParseText(code);

We can then create something called a compilation, to this compilation we can append syntax trees, references and other information that is valuable to our compilation. As the code that we want to compile uses Console we need a reference to that assembly, which is where System lives. This is what is called a metadata file reference, the compilation uses this when it analyses and compiles the code passed as a syntax tree.

The C# language has its specification and the parsing of the syntax tree adheres to this, however at this stage it is only represented as a syntax tree and nothing thus far is executable. This is why we need to add a reference to the assembly where the namespaces we use live. As the following code sample shows, we create the compilation, references an assembly and add the syntax tree.

var compilation = CSharpCompilation.Create("AnalyseMe")

.AddReferences(new MetadataFileReference(Assembly.GetAssembly(typeof(Console)).Location))

.AddSyntaxTrees(tree);

We still cannot execute the code, as nothing has been emitted to an executable. However we can ask for a diagnosis of the code or we can ask for it to finally be emitted so that it can be executed. When asking for the diagnosis we can see if the things found are just errors or simple warnings, if it is just warnings you can compile, but if it is errors you cannot. That is not actually the entire truth, you can emit the code that does not in fact represent a proper program, and there will be no errors of doing so. The result binary will just be 0 in size.

It is easy to ask for a diagnosis as you see here:

foreach (var diagnose in compilation.GetDiagnostics())

{

Console.WriteLine(diagnose);

}

If we remove a semicolor or a curlybrace from the code that we are compiling, you will see that the diagnosis will give different results.

The final step in this process would be to emit the code and make it runnable, as an executable binary. As easy as we got the diagnosis we can create an executable by emitting the code using compilation.Emit. This method has two overloads where one lets you specify the file location and the other lets you compile in memory to a Stream. Having the ability not to go to the disk each time you compile is something that makes the new compiler platform so enjoyable and super-fast!

compilation.Emit("test.exe");

The above will create an executable called test.exe which we can simply run and this will print Hello World to our console!

Below is a full code sample of the above code

using System.Reflection;

using Microsoft.CodeAnalysis;

using Microsoft.CodeAnalysis.CSharp;

using System;

namespace RoslynDemo

{

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

var code = @"

using System;

namespace AnalyseMe

{

class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

Console.WriteLine(""Hello World!"");

}

}

}";

var tree = CSharpSyntaxTree.ParseText(code);

var compilation = CSharpCompilation.Create("AnalyseMe")

.AddReferences(new MetadataFileReference(Assembly.GetAssembly(typeof(Console)).Location))

.AddSyntaxTrees(tree);

foreach (var diagnose in compilation.GetDiagnostics())

{

Console.WriteLine(diagnose);

}

compilation.Emit("text.exe");

}

}

}

Not only can we compile code with the Microsoft Compiler Platform, Roslyn. We can also analyse and manipulate the code that we have represented as a syntax tree.

What excites you the most about the Microsoft Compiler Platform, aka Roslyn?

Filip Ekberg is a Principal Consultant at fekberg AB in the country with all the polar bears, Microsoft C# MVP, author of a self-published C# programming book, Pluralsight author and overall in love with programming.

Filip Ekberg is a Principal Consultant at fekberg AB in the country with all the polar bears, Microsoft C# MVP, author of a self-published C# programming book, Pluralsight author and overall in love with programming.